5As of Ethical Living and Leading

The 5As are adapted from James Rest’s Four Component Model of Morality (Rest, 1982). Research indicates that competence in one of the first 4As does not necessarily predict competence in another (You and Bebeau, 2013). For example, a person could be excellent at moral reasoning (Analysis), but not actually follow through on their decisions (Action). Deciding what’s the right thing to do (Analysis) doesn’t mean it gets done (Action). The new 5th component (Adaptation) emphasizes the importance of reflection and continual growth. In order to develop as ethical leaders, we suggest focusing on all 5As. Want to better understand the 5As? See below and/or contact Nick Lennon, PhD (nlennon@gmu.edu) to request a workshop.

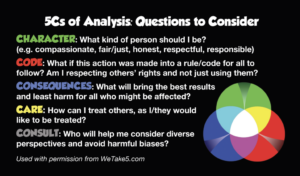

5As: Awareness, Aspiration, Analysis, Action, Adaptation

AWARENESS: Identify the potential impact on allIdentify the potential impact (ethical implications) on all who might be affected by this decision in both the short-term and long-term. Imagine a person who works at a clothing store. One day their boss asks them to memorize a script to convince customers to sign up for a store credit card. This employee is considering what to do:

- “Lower Level” of Awareness: “My supervisor tells me to push the store credit card by memorizing and delivering a script, so I do it without thinking twice about the impact.”

- “Higher Level” of Awareness: “I found out that store credit cards often have very high interest rates, high fees and can hurt credit scores. Also, I read that some scripts are misleading and hurt customer relations.”

Are you aware of the impact of your decisions on both yourself and others? Are you aware of how you, and others, typically approach decisions about what is right? It is important to recognize that many of our decisions have an ethical component. Not just very large or complex dilemmas like the death penalty or euthanasia, but also daily decisions such as “Should I be honest about my friend’s terrible new haircut the day before their big interview?”, “What should I recycle?”, “Should I get up and workout or sleep longer?”, “Should I steal a jet and fly to Indonesia for a hot stone massage?” As Prentice mentions: “Studies demonstrate that people are more likely to make poor ethical choices when they are barely aware that a decision has an ethical aspect.” Take5 each day to observe your emotions, gut reactions and thought processes. This will help you identify the ethical components of your decisions. See the Moral Awareness Video for more information about identifying ethical issues and the potential impact on all, in both the short and long-term. Note: as essential aspect of awareness is gathering facts.

Facts: Do you really have all the relevant facts? What evidence can help with our decisions? Where is the weight of that evidence? Do our facts come from good and reliable sources or are they mostly from unconfirmed internet postings, misinformation, fake news, personal biases (e.g., self-serving bias) or that guy who’s always looking under tables for used gum?